The Ross

Thomas Chronicles

"Perhaps

God and the Devil danced hand in hand around every single electron."

"Though Ross and I were too old to be hippies," Miss Harriet recalled, "it was the 1960s, and he and I were part of the Washington scene." Thomas, who was in his early thirties when the decade of the 1960s began, was three years older than his cousin Harriet. February marks the anniversary of what would have been Thomas’s 85th birthday. When the coquettish and quick-witted Miss Harriet first visited her Thomas in Washington D.C. in 1962, he was rebounding from a brief relationship with a woman of color. As for Thomas’s ethnic Washington muse, Miss Harriet attributed this phase of his romantic life as just one of his many "affectations." At the time, she was fleeing a twelve-year marriage to professor George Walton Webb, whom she had first met in 1949 at the University of Alabama. Some of Miss Harriet's closest friends have called the seemingly lackluster Webb "Zero," but at the same time understood her marriage to the distinguished professor Webb was a means of escaping from an overbearing mother in what had become a strained home life after the demise of her father. (Miss Harriet's sister Elizabeth was the childhood sweetheart of Katie Couric's uncle Bert "Buddy" Hene.). Despite financial hardship, Miss Harriet had attended Brenau Academy in Gainesville, Georgia for a year before going to the University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa. Her parents were Hattie Schuessler and the late Lewis Battle Dean, the youngest brother of Thomas’s mother Laura (a Phi Mu and Wesleyan), who’d taught art before her marriage to James “Ed” Thomas, an Alexander City transplant to Oklahoma City. Over the years the younger Thomas came a long way since first graduating from the University of Oklahoma in 1949 after serving in the U.S. Infantry during World War II. His first job was as sportswriter with the Daily Oklahoman. In the 1950s, Thomas worked in public relations for the National Farmers Union In Denver before establishing his own PR firm Stapp, Thomas and Wade, specializing in political campaigns, including George McGovern’s Congressional run. Abandoning his nine-to-five routine, Thomas next worked as a reporter for the Armed Forces Network in Germany and later as a representative for Dolan Associates in Nigeria. After returning to the United States from Nigeria in 1961, Thomas worked as a union spokesman for the American Federation for State, County, and Municipal Employees. According to Miss Harriet, at his very best Thomas was always "very liberal" and "politically active" and at his worst, an "Ivy-League wanna-be." By 1964, two years after Miss Harriet’s move to D.C., she and Thomas were sharing a house in a planned community in Virginia outside of Washington called Reston. In 1965, while working at Vista headquarters in Washington, Thomas wrote his first novel The Cold War Swap for which received an Edgar Award. Close personal friend Mrs. Nancy Gwaltney of Alexander City says, "Harriet told me when she lived with Ross he got both free housekeeping and free proofreading. Her dad Lewis and my father were best friends. We used to go to Ft. Walton Beach together." Legend has it that Lewis Dean, who during the Jazz Age frequented Montgomery with his brother and their friend Leon Frohsin, dated Zelda Sayre. Early on, Lewis’s nephew Thomas had been signed by Otto Penzler, who believed at the time Thomas was ready to "break out." (Penzler later published six of Patricia Highsmith’s novels in the early 1980s.) Thomas faired better with Penzler than did Highsmith, who in 1987 signed with Atlantic Monthly Press after reluctantly agreeing to Penzler’s demand that she drop from the American editor her dedication to the Palestinian people in the European edition of People Who Knock at the Door. A year after the publication of The Cold War Swap, the cousins were back in D.C. Miss Harriet claimed to be the inspiration during this time for both Thomas's pseudonym and for characters in his novels. She says they dreamed up the name Oliver Bleek -- a nod to Charles Dickens with Oliver for Oliver Twist and Bleeck for Bleak House -- during a road trip down south for a family funeral, and that she also coined for him the phrase "Diddie, Dumps & Tot," which is the title of Diddie, Dumps & Tot or Plantation Child-Life by Louise-Clarke Pyrnell. Thomas, said Miss Harriet, was unfamiliar with the old stories, legends, and traditions of the southern slaves. It was around this time that Thomas's mother Laura also passed away. According to Thomas’s and Miss Harriet’s cousin Kathryn Dean, Thomas and his adopted brother James "Jimmy" quarreled bitterly after Mrs. Thomas’s death. Dean explains that after graduating from Auburn, she’d worked briefly at Rich's in Atlanta, and then her aunt and uncle -- Thomas’s parents -- came to visit from Oklahoma. "Uncle Ed was a builder," explains Dean, "so I moved to Oklahoma City and worked for him briefly." (Thomas’s father died in 1960.). At the time her Aunt Laura died, Jimmy wanted his mother buried in Oklahoma City, and Thomas wanted her buried in the family plot at Alexander City; in the end Thomas won out. (In World War II, Jimmy served on the U.S.S. Sterett and was at Guadalcanal.)

Miss Harriet had carried the same old, though once expensive, leather bag for most of the time she'd taught inner-city children, but previously one of her classes had surprised her with a new, shiny plastic bag to replace the worn one. On that day in April, facing a long train ride home, Miss Harriet clutched her tawdry, yet beloved, bag and grabbed hold of the sleeve of a female African-American co-worker, and the two rode together to her stop. Thomas, who had gone home to check on her, was relived to see her safe, as the riots lasted for four days. Toward the end of 1960s, Reston was remembered as a respite for the cousins. Thomas began co-writing, with national director of the VISTA William Crook, Warriors for the Poor: The Story of VISTA, Volunteers In Service to America. By then Thomas and Miss Harriet were often begging to differ over cocktails, and by 1971 there was a rift in their relationship. The final straw was the entrance of Rosalie Appleton, a librarian at the Library of Congress, who became Thomas’s new muse and the love of his life. With Thomas’s former co-worker Betsy Levinson Bilanow, her children, and Rosalie, the situation now encompassed one large extended family. (There was no longer room for Cousin Harriet in Thomas’s life.) Betsy was married to Alexander Bilanow, columnist for the Washington Daily News and later a reporter for the Washington Star. Betsy, who later went to work for B'nai B'rith, once told Miss Harriet of the day she slipped away from the office to go shopping on September 11, 1977, shortly before a well-coordinated terrorist attack against the organization took place in the nation's capital. (Heavily-armed gunmen, Hanafi Muslims, carrying shotguns and machetes, stormed into the district building on Pennsylvania Avenue.) One of the Bilanows’ sons was so enthusiastic about Thomas’s engagement to Rosalie that he baked the couple a wedding cake when they married in 1974. Shortly thereafter, Miss Harriet became Mrs. Martin Levy and spent time in Majorca. Mr. Levy, whose family was in the retail business in the D.C. area, was quite different from Miss Harriet’s first husband, who was not well liked by some of her southern friends. As for the Levys, the newlyweds found Majorca different from that which they’d imagined. The days of running into Patricia Highsmith or Robert Graves in Deią were gone. By the time Highsmith canceled in September of 1987 what would have been her final trip to the island (for which she was supposed to have written a travel piece for the Sunday Times) the Levys had departed for home. Their idle in Majorca was colored by Heineken’s now famous ad slogan, "The water in Maj-jaw-ka, don’t taste like it oughta." So, the Levys fled the "package-holiday" overload of Majorca's building boom and returned to the States. Mrs. Gwaltney says she was fond of Mr. Levy, who once accompanied his wife Harriet to dinner at the Gwaltney home in Alexander City. "Harriet had a hard life, but she was a good student and liked school. We would often have supper together and talk about 'old' Alexander City and all its characters." Thomas went on to write the screenplay for the Laurence Fishburne film Bad Company and the story for the Benjamin Bratt film Bound by Honor. He is also credited with the "Sacrifice" episode for Tales from the Crypt and nine episodes of Tales of the Unexpected, including "Youth from Vienna" and "Bird of Prey," as well as episodes of Simon and Simon and Hardcastle & McCormick. (Additional credits to his filmography include Blood In, Blood Out and Hammett.) In 2002 Thomas was honored with the inaugural Gumshoe Lifetime Achievement Award, one of only two authors to earn the award after their death (the other was author Evan Hunter). And as recently as the summer of 2010, Thomas made the Top 200 finalists in National Public Radio's "Killer Thrillers" contest with his Chinaman’s Chance, featuring Arthur Wu and Quincy Durant, one of southern California's most unlikely pairs of detectives. And his Briar Patch was earlier listed in Mystery Muses: 100 Classics that Inspire Today's Writers, edited by Jim Huang and Austin Lugar. Miss Harriet always kept a small cardboard box with her that contained handful of old photographs and a letter from Thomas. As for her correspondence to him, it was destroyed in a fire at his Malibu home, along with many of his other personal papers. But before Thomas's death in 1995, Miss Harriet heard his voice on public radio one last time, and the man who has been described by friends as the "love of her life" surprised her with "a fake southern accent." He "pulled it off," she admitted, despite the fact that he'd had a distinctive mid-Western accent at the time he lived her. This marked Thomas's last appearance on national radio. (He is buried at Fairlawn Cemetery in Oklahoma City with his father and brother.) Miss Harriet wondered if perhaps the Pyrnell book may have prompted Thomas's reinvention on public radio as "a southern gentleman" or if, in part, he was inspired by the short-lived Confederate service of their grandfather. Miss Harriet thought there was nothing gallant about their grandfather's contribution to the Cause, as he entered into the fray late in 1864. But the ever-impressionable Thomas was touched by the last-minute gesture of his grandfather, until then deferred as a "civil officer" and "constable." “Harriet worked with Bill W. 'Billy' Buchannon," recalls Thomas Byron Saunders, former editor of the Russell Record (the company newspaper of Russell Corporation). "Billy had a paper called the Alexander City Citizen, which started in 1972. I went by to give Billy an article about the Russell folks, and Harriet was there sitting on the floor proofreading. Later she asked if she could come to work with me, and we worked together for a year. Then she worked with the Alexander City Outlook into the early 1980s." As it turned out Miss Harriet, who had divorced Mr. Levy, became an award-winning writer in her own right. She won an Alabama Press Association Award for her columns in the Alexander City Outlook. Gradually Miss Harriet's small circle of friends dwindled to a socialite and textile heiress; a childhood friend (and the son of a local judge); a Memphis native, who was both friend and caregiver; and a retired college professor, who attended Miss Harriet’s church and delivered flowers to her assisted living facility. She died in early 2009 and her memorial service, held on Martin Luther King Day of that year, was attended by a small gathering of fellow churchgoers and friends, including the daughter of the late Betsy Bilanow. None of the family were able to attend. "Harriet was always interested in writing," recalls friend and caregiver Mary Dee White of Alexander City, who adds Miss Harriet was always reticent in discussing her relationship with Thomas, "and she shared her ideas about books with me. We met in 1980 at St. James Episcopal Church and became friends through our work on the church newsletter. It was a joy to talk with her about her teaching jobs and her travels." "I didn’t know her as a teacher," concludes Saunders, "but she was very well read. She was very sensitive to the English language and very conscious of sentence structure and had a sensitive ear for the English language and its beauty. This typifies her more than anything else." As for Miss Harriet herself, till the end she was self-deprecating, while lauding Thomas's talents. At the close of her life, Miss Harriet exercised her pointed wit, no doubt honed during the years she spent with Thomas. She once played off the title of Thomas's 1973 novel If You Can't Be Good. "If you can’t be good," she quipped, "then write well." And that Ross Thomas did. |

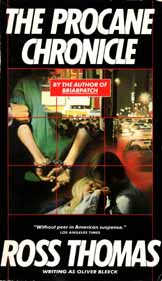

Over the years both eyebrows and questions have been raised

about the nature of the relationship between mystery writer Ross Elmore

Thomas and the women who were his muses. One of those was his first

cousin Harriet Dean Webb Levy of Alexander City, Alabama, who, before

her death, talked freely about the "affinity" she always shared with

Thomas, whose novel The Procane Chronicle became the Charles

Bronson film St. Ives.

Over the years both eyebrows and questions have been raised

about the nature of the relationship between mystery writer Ross Elmore

Thomas and the women who were his muses. One of those was his first

cousin Harriet Dean Webb Levy of Alexander City, Alabama, who, before

her death, talked freely about the "affinity" she always shared with

Thomas, whose novel The Procane Chronicle became the Charles

Bronson film St. Ives.